Still a couple more hours for the year 2020 to end. A year in which so much was lost — our freedom to go where we like and meet whom we want, jobs, health, and the lives of too many friends and family members.

I feel that science has lost something as well — credibility with the general public because of the back and forth on some issues regarding COVID-19 prevention and treatment. It is hard to explain to non-scientists how difficult and slow science sometimes is, especially in light of a new virus, a new pandemic. Good science is often slow, but we all wanted fast answers, and this brought a lot of “Yes we found it!” and “Oh, well, never mind” papers that were confusing to understand or explain. In addition, the current US government has not been very science friendly, encouraging false statements to confuse many of us.

Still, there are some hopeful signs. The first coronavirus-vaccines are being distributed and a new US government will hopefully restore some of the faith in science that has been lost in the past years.

Here, I look back on the work in science integrity that I did in the past year. All the work I list here was unpaid, and I thank my loyal Patreon subscribers for their ongoing support that allows me to keep on doing my volunteer work.

My current work

Since the summer of 2013 I have found 4,541 scientific papers with plagiarism, image, data, or ethical concerns. Most of these — 4,244 papers — have been reported on PubPeer (n=3,563) and/or to journal editors and academic institutions. I am still trying to catch up with the ones I have not yet reported or posted, but most days bring requests to screen more new papers than I can handle.

Since I quit my full time job in March 2019, I have been able to work full time on science integrity. I am still following up on leads from the 800 papers I found during my scan of 20,000 biomedical papers with photos (published in mBio), but most of my time goes into investigating papers sent to me through email or social media.

Sometimes, I get requests to look at a single paper, while others ask me to “just” screen all 200 papers by Dr. X. Often, one suspicious paper will lead to another, or to new ideas to screen for duplications, paper mills, or conflicts of interest. There is never enough time, so I sometimes have to turn down requests for help. I always feel bad about this.

A big thank you

In several of these projects I have worked together with other image duplication detectives, such as SmutClyde, Tiger, Cheshire, Morty, Clare Francis (all pseudonyms), and several anonymous others who cannot be named, as well as with science journalist Leonid Schneider (ForBetterScience). I thank them all for their invaluable and often uncredited work.

I would also like to thank Adam Marcus and Ivan Oransky of Retraction Watch for fantastic reporting on scientific retractions and the stories behind the scenes. Their reports reveal the sad and depressing circumstances behind some of these cases — something I always try to be aware of.

A big thank you also to others working in similar areas around science integrity, such as Dorothy Bishop, Nick Brown, James Heathers, Debora Weber-Wulff, Paul Brookes, Kaoru Sakabe, Sylvie Coyaud, Jennifer Byrne, Jana Christopher and the PubPeer founders.

What did I do this year?

More than half of the 3,563 problematic papers I have posted onto PubPeer since 2013 were posted there in the past year: 1,905 papers. I have been busy, as you can imagine! Some of these posts were for papers that I had already reported to journals in the past. I am trying to post many of these onto PubPeer, so people who have installed one of the PubPeer browser extensions are aware that a paper might have some concerns, even if that paper has not been corrected or retracted.

I also officially reported 750 papers to their journals and institutions. Unfortunately many of them never respond, or if they do, are slow to take action.

Individual pearls

Some remarkable papers that I found in the past year:

- A paper claiming that 5G waves could penetrate skin cells and program to make coronavirus DNA was my personal Worst Paper of 2020. It got retracted within days, but the journal with its ghost ship of dead editors still continues to publish some peculiar papers.

- A paper with photoshopped pieces of Melba toast, written by the Surgisphere founder during his PhD years, is unfortunately still standing strong. Neither the journal nor the university wanted to touch it. For this the University of Illinois won the “This Image Is Fine Award“.

COVID 19

The Coronavirus pandemic resulted in an avalanche of papers — too many of which were not great. The one that got a lot of attention — and even a presidential tweet — was the March 2020 paper by Guatret et al. in which it was claimed that hydroxychloroquine + azithromycin were very effective in reducing viral load. I wrote a critical review of the paper pointing out many concerns — but it is still standing as of today.

Paper mills

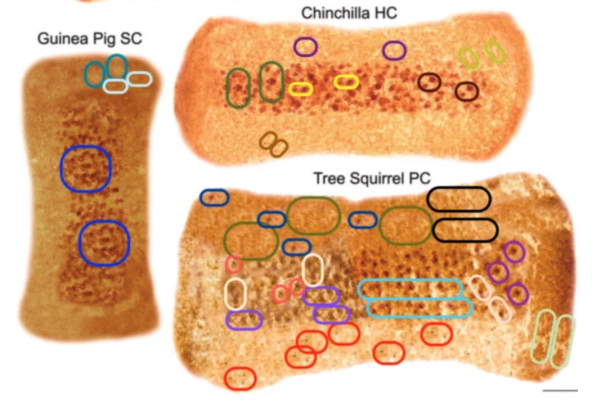

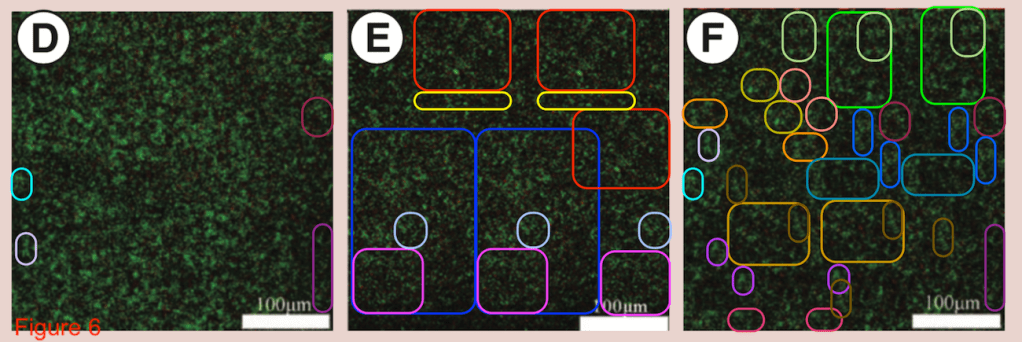

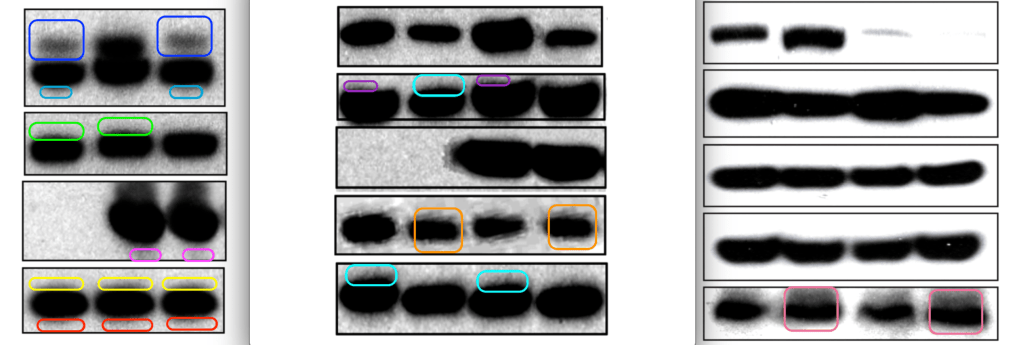

At the start of 2020, we worked together as a small group of image detectives to uncover a large set (currently 550) of papers that all appear to contain Western blots with the exact same background, often accompanied by hairball-like flow cytometry plots. These papers all appeared to have been made in the same studio, from where they were sold to customers at different hospitals in China who needed a published paper for their medical career. We called this the Tadpole paper mill, and our work gained a lot of attention (Science, Nature, The Wire).

In June and July I worked on a set of more than 120 papers, all from different researchers working at Chinese hospitals, that appear to use the same set of photos. I called these the Stock Photo Paper Mill set. This work was covered by the Wall Street Journal in July.

Sets of papers by the same research groups

This year also brought some large clusters of cases from the same research groups. Here are the largest sets I worked on this year.

- In January, 18 papers from a group at Sichuan University in Chengdu were found to contain overlapping images or repeated features within the same photo. Three of these have since then been retracted.

- At the beginning of March, I worked with several others on a set of about 50 papers by researchers at the University of Rochester, UC Davis, and University of Pittsburgh, partially funded by the National Institutes of Health. More details can be found in this blog post.

- After sharing my concerns about a COVID-19 / hydroxychloroquine paper from a lab in Marseille (see above), several stories were shared about questionable practices in that lab. I found a bunch of problems in other papers by that group, which led Didier Raoult, the head of the lab, to label me a “witchhunter“, and a “cinglée”.

- Also in March, I reported nearly 60 papers by a researcher at Northeastern University working on nano- (and pico-) technology. Leonid Schneider wrote about those papers here.

- In April, I reported 23 papers from a researcher who first worked at the University of Michigan, then later at UCLA; one of these papers got retracted in November.

- Also in April, Nick Brown wrote about a researcher who appeared to have made up a large data set on 10,000 African gamers, a paper in Scientific Reports that got quickly retracted. Digging a bit further, more papers by this researcher appeared to contain problems, ranging from improbable datasets and re-used data, to co-authors that do not appear to exist and excessive self-citation.

- In August, papers from a research group at Dumlupinar University were brought to my attention. Details can be found in my blog post here. I reported a set of 84 papers by this group; two of these have since been retracted.

- August was also busy with reporting a set of 15 papers by a researcher who worked at several universities in the US, mostly on National Institutes of Health grants.

- In October I worked on a set of papers from a person who claims to work at the California South University, an institution that does not exist. Many papers contain images copied from other researchers and hundreds of citations by the first author. Most were published in predatory journals.

- November brought a large set of papers (numbering 45 as of today) by a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, mostly containing duplicated Western blot panels or lanes.

- Another set of 28 papers from a lab at the University of Louisville was reported in November as well.

- In November, I also worked on nearly 50 papers from a director at the Royan Institute that appear to contain duplicated figure panels or duplications within the same photo. Another subset of papers appears to match claims in patents which were submitted before the paper was published, but where the authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

- December was filled with finding and reporting on 45 papers from a research group at Tianjin Medical University.

Memorable 2020 Retractions

Since I started working on science integrity in 2013, the 4,500 or so problematic papers I’ve found have led to 347 retractions. More than half — exactly 200 — of these happened this year. This shows how patient you need to be in this work, and demonstrates that journals have been slow to respond. A large chunk of these retractions were published in the European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences journal, which was infected by the ‘Stock Photo Paper Mill’, and was quick to act.

Here are some other memorable retractions from this year:

- As mentioned above, the “5G/Coronavirus” paper that I and many others criticized, got quickly removed. Some other papers by the same authors also got retracted, such as a paper claiming there is a black hole in the center of the earth, where new DNA gets generated, and another paper stating that chickens have a second brain in their heart so you can just chop their heads off.

- A 2007 Science paper from a Dutch top-institute, which I already reported to the journal in 2015 for image manipulations, finally got retracted in 2020.

- A paper with possible duplicated parts of Western blots — suggestive of photoshopping — published in Nature, got retracted in June 2020 after I tweeted about it in August 2019.

OK, the year is almost over, so I am going to open a bottle of bubbly and put on my festive top and wish you all the best for 2021.

Here’s to lots of high-quality science!

Congratulations on a successful 2020! We appreciate all that you do.

LikeLike

I think it would be great if you could also say how many papers you flagged but the editors were not agreeing with you and will not retract that paper. It would nicely complete your statistics, e.g. 4500 papers flagged, 350 retracted but X papers of the flagged will not be retracted.

LikeLike

Thanks for the feedback! That would be a tough statistic to add, for several reasons. First, I lost my correspondence from 2016 and before, so I do not have the initial responses by the editors. Then, in several cases, editors would agree with me but not retract because the paper was more than 6 years old. Or, editors might agree, but not want to retract because the authors did not respond, or because the authors send in a new set of photos and the editors would just issue a correction. Also, there have been several cases where the editors either did not respond but retract, or responded but not retracted; so editors’ responses are not always indicative of what will happen. And finally, there have been cases where the editors initially did not want to retract for various reasons, but then, years later, will retract after I discussed it on Twitter.

LikeLike

Best wishes for 2021!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Same for you, Smut!

LikeLike